Taste of history: UGA Heritage Apple Orchard now bearing fruit

ATHENS — On a fine day at the University of Georgia Heritage Apple Orchard, you can see the fringing peaks of the Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest rising around like a hedgerow, guarding against whatever forces might encroach.

When Stephen Mihm looks over the tops of the 275-odd dwarf apple trees that constitute the orchard, he sees more than a pretty view of the Appalachian foothills. He sees clear into Georgia’s past.

“These mountains were a center of commercial cultivation,” Mihm, a professor of history and associate dean in the Franklin College of Arts & Sciences says, gesturing at the landscape. “We were growing these apples, many of them, that you see around you. Every tree you see is a variety of apple grown in Georgia at some point in the distant past, typically before 1920.

“The vast majority of them, you cannot find anywhere now in Georgia. Except on this hill.”

Planted three years ago during a global pandemic, the trees of the Heritage Apple Orchard are now producing fruit and well on their way to helping Georgia rediscover part of its agricultural legacy. Its 139 apple varieties represent a tantalizing pip of possibility: the revival of Southern apple culture, in all its former glory and complexity.

Before it was reinvented as one of sport’s most iconic structures, the clubhouse at Augusta National was surrounded by acres and acres of fruit trees. Fruitland Nurseries, founded in the 1850s by Belgian immigrants, was one of the Southeast’s largest 19th-century horticultural operations. Its 1860 catalog listed 900 varieties of apple tree, 300 varieties of peaches, and 1,300 pears.

After Fruitland closed in 1918, golfing legend Bobby Jones and his business partners purchased the property and turned it into the most famous golf course in the world, with the nursery’s former manor house now serving as clubhouse.

Fruitland may have been the pinnacle of Southern horticulture, but similar, smaller operations dotted the valleys of the Blue Ridge from Georgia to Virginia. Southern farmers both large and small served their local communities, growing a wide range of seasonal produce that included literally hundreds of apple varieties.

“In the South, we could eat apples, fresh apples without refrigeration [virtually year-round], from May through April [because of the different varieties],” Diane Flynt, author of “Wild, Tamed, Lost, Revived: The Surprising Story of Apples in the South” and owner of Foggy Ridge Cider in Virginia.

As in so many industries, technology brought irrevocable change. Railroads began crisscrossing the country, hauling fresh apples to markets previously unreachable. Advances in storage technologies — such as refrigeration and controlled atmosphere storage, in which oxygen levels are kept low to slow ripening — meant that Carolina Red Junes and other early-season favorites could be kept fresh and enjoyed well into fall and winter.

Southern apples also fell victim to social and economic changes. Prohibition drove the cider and apple brandy producers underground. Growers discovered they could maximize revenue with denser orchards of fewer varieties, reducing costs by instituting uniform maintenance practices rather than catering to a wide range of particular needs.

By the early 20th century, the bulk of U.S. apple production had moved north to states like Washington and Michigan, and the industry’s focus on a small number of varieties led to a homogenization of consumer tastes. Southern growers tried to plant what consumers wanted — apples that grew well in northern climates — with limited success.

By the 1920s, the Southern apple industry was a fraction of its former size. It would never recover. Or would it?

The Heritage Apple Orchard can trace its origins to real estate transactions. Both Mihm and Josh Fuder, the UGA Extension agent for Cherokee county, became interested in heirloom apples after they bought houses with apple trees already growing on the property. The history of those trees intrigued both enough for them to reach out individually to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Plant Genetics Resources Unit in New York, which connected them to each other, and the idea for the orchard was planted.

The pair worked to assemble DNA of heirloom varieties in the form of scion wood — cuttings from living trees — sourced from the USDA, from individual contacts still maintaining old trees, and from well-connected growers and nurseries in the Southeast.

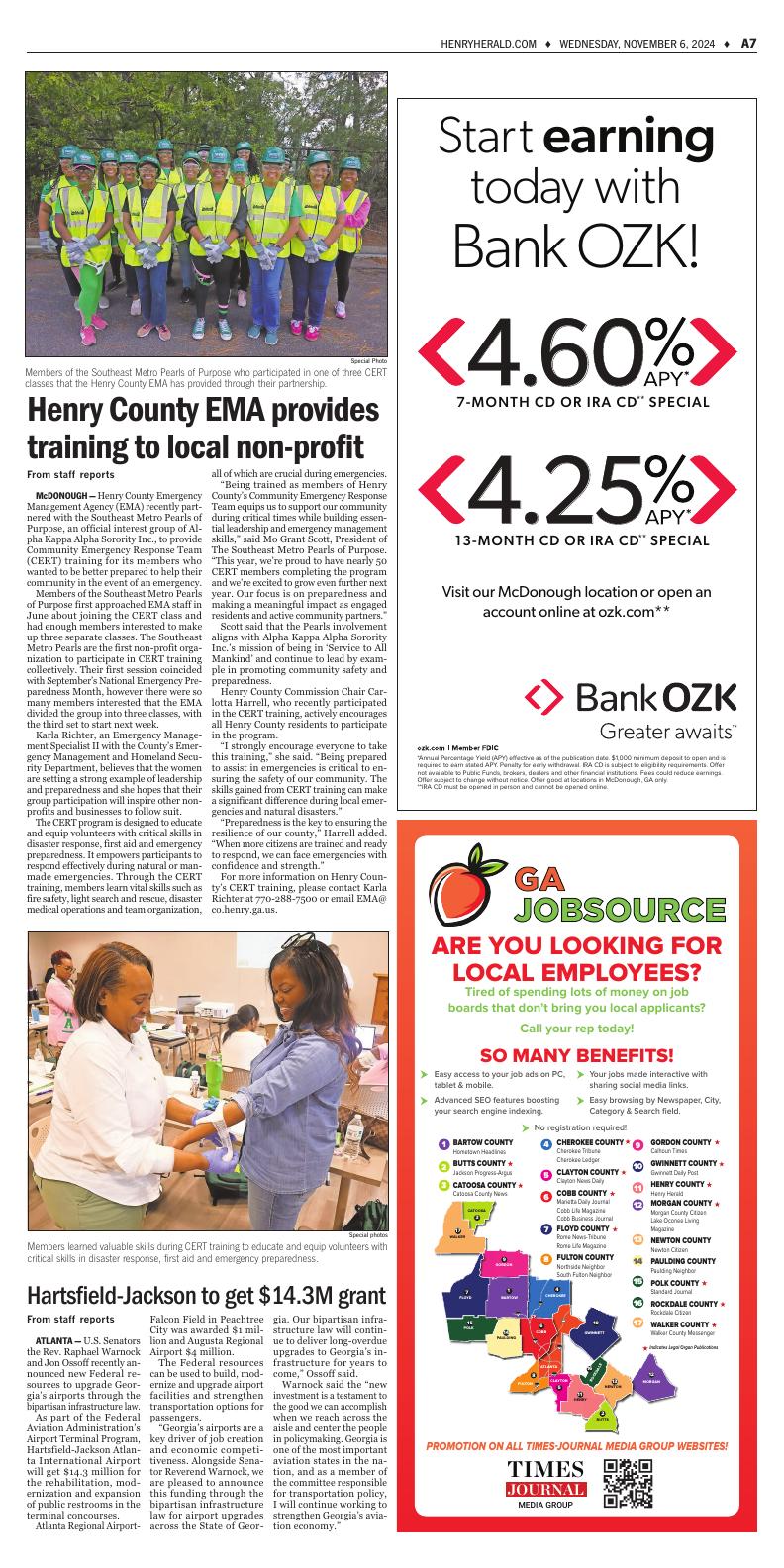

UGA Extension officer Josh Fuder (fourth from left) taught the 2020 workshop in which volunteers grafted the Heritage Orchard’s scions to dwarf rootstock, then helped put the saplings in the ground a year later. In early 2024 he led this crew of fellow Extension officers to Blairsville to prune and evaluate the orchard’s young trees.

Ray Covington, superintendent of the UGA Mountain Research & Education Center in Blairsville (a unit of the College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences), offered a couple of acres for the new orchard. The center was long acquainted with apple production, having grown stands of contemporary varieties for decades.

In 2020 — just a week before COVID-19 shut the world down — Fuder led a workshop to graft the heirloom varieties to rootstock. They grew in pots for a year until February 2021, when a group of facemask-clad volunteers lent their labor to get the trees in the ground.

“These trees all have their own individual personalities,” Covington said. “There are 139 varieties on the property, and they’re all different. They bloom at different times; they have different growth habits; they’re ripening at different times.”

Because named apple varieties are always reproduced through grafting — apple trees grown from seed rarely produce the same kind of fruit as their parent trees — the pairs of Newtown Pippin and Hewe’s Crab growing at the Heritage Orchard are genetically identical to the trees described in Jefferson’s and Washington’s journals.

But the provenance of other rediscovered varieties is much less clear, and that’s why Mihm looks forward to working with plant scientists to do genetic testing on the trees, both to discover commonalities with other known varieties and to isolate genes associated with beneficial traits such as heat tolerance and disease resistance.

Even the precision of modern genetics, however, may not solve all the mysteries.

“The challenge in a lot of these lost varieties is, yes, we have DNA testing now, but a lot of the Southern apples are not in the backlog of genetic data,” Fuder said. “So even if we sent our Family variety for testing, that may be the only one they’ve ever tested and it would come back as unknown, or sharing the same parents or grandparents as another variety. But they wouldn’t be able to tell us, ‘Yeah, you’ve got Family there.’”

Drew Fitchette has a rule of thumb for cider apples: “The uglier the apple, the better the cider.”

Fitchette is an aspiring cidermaker from Atlanta who heard about the Heritage Orchard, and on a fine day in early September made the trek up to Blairsville to see the apples for himself.

“Only bold flavors survive the fermentation process,” he said. “I’m interested in finding Southern apples with the sort of tannins and acidity that would make it through that process. Most of these old apples have characteristics that have been bred out of more popular varieties.”

Rare and unique flavor profiles are important for cider, but even more vital are essential characteristic like susceptibility to disease and an ability to handle hot, humid Southern summers.

Three years into the ground, the trees are proving history correct. The Heritage Orchard is planted next to several thick rows of Golden Delicious, which are suffering from Glomerella leaf spot, a fungal disease common to apple trees, and being treated heavily with pesticides and other chemicals. The heirloom cousins growing beside them show no sign of sickness.

“We are starting to observe some standouts, some truly disease-resistant varieties,” said Fuder, who over the summer led a team of extension agents to inspect and grade the trees. “We just went through tree by tree and gave them scores.

“After all, what good is a nice tasty apple if we can’t grow it here?”

The orchard keepers have kept in touch with larger apple growers from Ellijay and Blue Ridge, who certainly will play a role in any revival of Georgia apple culture. Even if a small cidermaker like Fitchette wanted to work with UGA’s apples, Mihm said, they likely would contract with a commercial orchard to devote a section of its acreage to the heirloom varieties.

“Commercial growers want to see the fruit — they want to see a bushel of apples in front of them and taste them. We’re still in the early stages. This beautiful tree right here,” Covington said, gesturing to a King David, “is on its third year, maybe fourth year. It’s nice and tall, but it’s still not a full-producing tree.”

That won’t be the case for much longer. The Heritage Apple Orchard soon will boast mature trees whose branches will be laden from late May to November with apple varieties that have not seen the Georgia sun since before the first World War.

For those who brought the Heritage Orchard to life, the future is sweet indeed.

“If we’d scheduled our grafting workshop just two weeks later in 2020, the orchard would not have happened [due to the COVID-19 lockdown],” Mihm said. “There were just many, many obstacles. To see an orchard — a very large orchard, at that — happily growing despite all the trials and tribulations, and now coming into its own to achieve the ends we hoped, is extremely rewarding.”